Oliver Neve, Lora Brill, Dale Tromans, Jukka Lahdensivu

December 4, 2025

Design codes: The Trojan Horse of climate resilience

Climate change is no longer something we can avoid. It is now something we must learn to live with. As global temperatures continue to rise, the real question becomes how we adapt, endure, and navigate the shocks ahead.

Some impacts of climate change are now impossible to avoid. The UN chief, António Guterres, has acknowledged it is now “inevitable” that humanity will overshoot the target set in the Paris climate agreement, and the UK's Climate Change Committee has told the government to prepare for 2°C of global temperature rise by 2050.1

So, the question shifts from climate mitigation alone to how we navigate the changes that are here and accelerating. This article does not address the ongoing efforts to limit climate change, although it remains a critical goal for humanity. It focuses on how we can endure climate change and navigate the shocks ahead.

We all know the story of the Trojan Horse; the Greek myth of an innocuous wooden horse used to infiltrate and ultimately destroy the city of Troy. The Trojans welcomed the horse, rolling it within the city walls and underestimating the threat that lay within. Our industry does something similar with design codes. We embrace them, give them pride of place, and assume resilience is factored in. But the horse holds surprises: stationary assumptions, update cycles that lumber, fragmented hazard treatments, and a habit of smoothing over compound risk. If we fail to pull off the panels and look inside, we risk building tomorrow’s failures today.

In this article, we look at the risks, the problems hiding in today’s codes, and what can work instead.

Is there a Trojan Horse hiding in today’s codes?

A case study: Finland

Finland's average annual temperature has risen by approximately 2°C since the early 20th century, which is about twice the global average rate of warming. In line with the EU's Taxonomy criteria, we conducted a Climate Vulnerability Risk Assessment on 54 buildings completed during the last five years. These buildings were constructed according to current codes and include mostly residential apartment buildings, as well as hotels, office buildings, schools, and kindergartens.

Despite being no more than five years old, the evaluated buildings exhibited several physical risks in present and projected future climate (RCP8.5 20502). These risks could be mitigated during the design and construction phase if codes reflected the predicted temperature increases based on current science.

The most significant risks for new buildings are thermal stresses and heatwaves, which increase the interior temperatures. Wind-driven rain presents significant risks to external walls, roofs, and roof terraces for most evaluated buildings. Several structures and details used in these buildings were inadequate in terms of building physical performance, allowing water leakage inside without sufficient drying capabilities.

[2] RCP = Representative Concentration Pathways, 8.5 scenario = the highest increase of emissions, 2050 = the year climate was projected. These are based on CMIP5 model data, while newer SSPS5-8.5 (SSP = Shared Socioeconomic Pathways) is based on CMIP6. For the purpose of this case study, RCPs were used. This is because the Finnish Meteorological Institute’s wind-driven rain and the amount of rain calculations were based on the older model.

Where risk creeps in – How we use climate futures

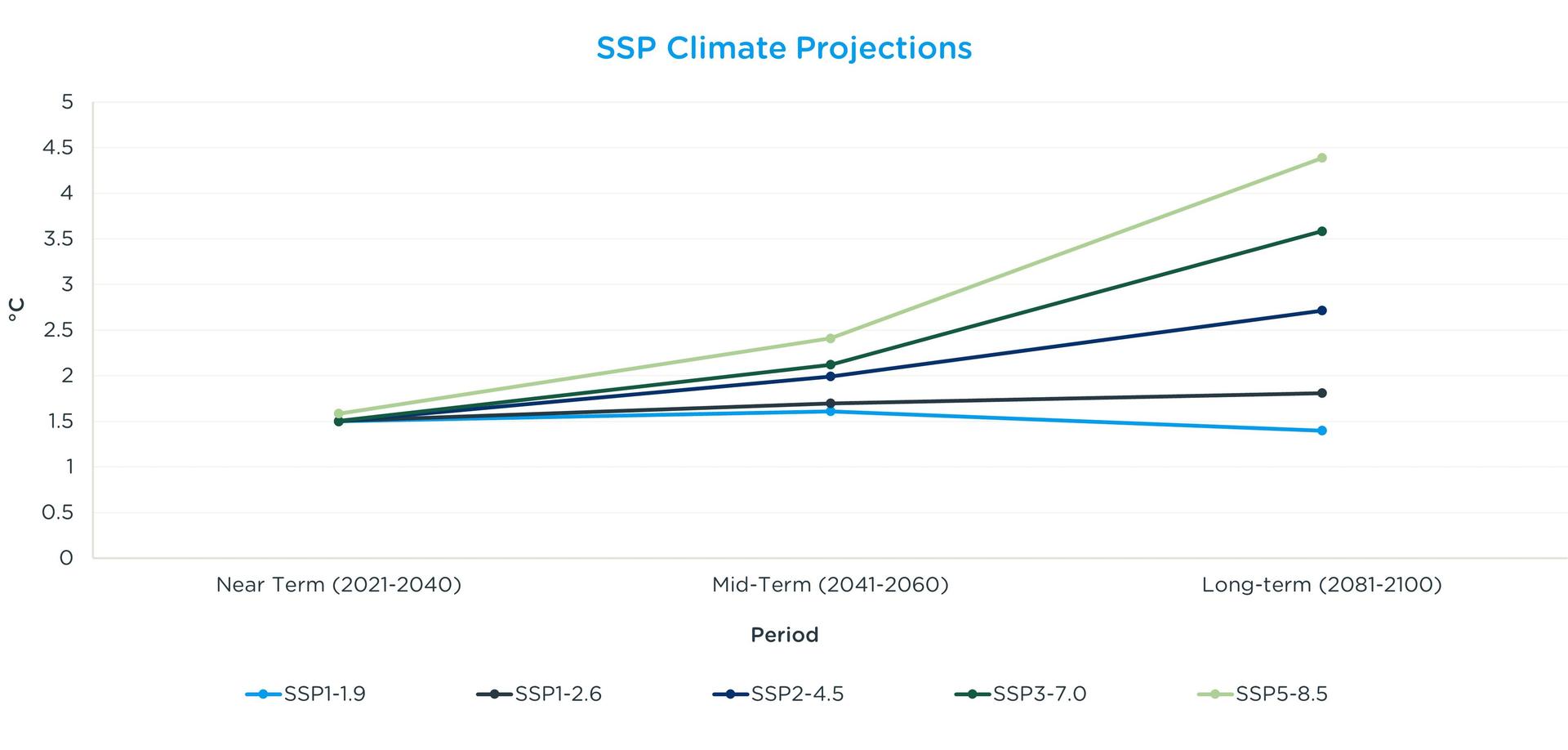

Making future predictions about the climate is challenging. Climate modelling is complex, and outcomes depend on socioeconomics, technology, policy, and land-use. To understand the range of futures that could occur, climate practitioners use scenarios developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). These Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are commonly summarised as:

- SSP1-1.9 (Sustainability): Very low emissions; closest to a 1.5°C world by 2100.

- SSP1-2.6 (Sustainability): Low emissions; approximately 2°C by 2100.

- SSP2-4.5 (Middle of the road): Intermediate path; emissions plateau then decline but not to net zero by 2100.

- SSP3-7.0 (Regional rivalry): Medium-high emissions with fragmented geopolitical progress.

- SSP5-8.5 (Fossil-fuelled development): High emissions driven by intensive fossil fuel use.

Given this range, codes and regulations can – and should – explicitly reference scenarios, time horizons, and asset design lives. There are many plausible futures, so practitioners test performance across multiple scenarios and periods (e.g., 2030s, 2050s, 2080s), not just a single point estimate. Due to uncertainty and the long life of assets, a range-based approach with adaptive strategies is essential.

The Trojan Horse problems hiding in today’s codes

Design codes are meant to keep people and infrastructure safe. Yet in a rapidly changing climate, some of the very assumptions built into today’s standards can create blind spots. Hidden within them are vulnerabilities that quietly increase exposure to future climate risks. These “Trojan Horse” issues are not obvious at first glance, but they sit inside many of the codes we rely on every day.

1.Most standards use historical data and statistics

Many design actions are derived from historical observations under an assumption of stationarity, that yesterday’s climate is a good guide to tomorrows’. For instance, wind, snow, rainfall, and temperature loads often use historic return periods (e.g., 1-in-50-year events) calculated from past datasets. In a non-stationary climate, those return periods shift and what used to be “rare” can become regular within the life of the asset.

2.There is a lag between standards and accelerating climate risks

Standards bodies do revise codes, but the cycle of research, consensus, drafting, consultation, adoption, and enforcement can take years. Climate hazards are evolving faster than many update cycles. Even where forward-looking guidance exists, adoption by jurisdictions can lag, creating a patchwork of requirements where resilience is often optional rather than prescriptive.

3. Projections are not granular enough

Design needs local, asset-relevant variables, such as rainfall intensities, wet-bulb temperatures, compound flood drivers (pluvial + fluvial + coastal), heat island effects, wildfire spread, and drought persistence. Many projections are coarse in space and time, and this downscaling through codes adds uncertainty and risk.

4. Cherry-picking climate scenarios and horizons

A common pitfall is mixing aggressive scenarios with near-term horizons or vice versa and claiming robustness. For example, using SSP5-8.5 for the 2030s may look conservative, but the spread across SSPs is relatively small up to about mid-century; the divergence explodes beyond 2050. If an asset’s life extends to 2080 or beyond, a single “2030s high scenario” check does little to inform the end-of-life performance. Conversely, using a low scenario for a long-lived critical asset can understate tail risks.

5. Fragmented treatment of compounding and cascading risks

Standards tend to silo hazards: wind here, snow there, heat somewhere else. Real-world failures often involve compounding drivers (e.g., storm surge plus fluvial flow plus heavy rainfall) and cascading impacts (power outage → cooling failure → indoor overheating). Codes rarely require multi-hazard, compound-event stress tests across future climates.

Why the traditional approach no longer works

In a rapidly changing climate, long-held assumptions begin to break down. Historical return periods no longer reflect the frequency or intensity of future hazards. Assets designed to last 50 to 100 years will face late-century conditions where extremes and scenario divergence matters most. Relying on traditional safety factors cannot compensate for shifts in hazard patterns, nor for the socio-technical complexity of modern systems, where small errors can trigger cascading failures across infrastructure networks. In short, the old model of designing for yesterday’s climate is no longer fit for purpose.

What a better approach looks like

A more resilient design culture is possible, but it requires embedding future climate conditions directly into our standards and processes.

1. Make future climate explicit in codes

This requires the use of multiple SSPs, time horizons, and local guidance aligned to design life, while documenting why those scenarios, sources, and assumptions were chosen.

2. Move toward performance and resilience-based design

We should define the levels of service and survivability an asset must maintain under future extremes.

3. Improve granularity and traceability

Regionally downscaled datasets and, where needed, bespoke modelling can translate climate projections into engineering-relevant variables, complete with uncertainty ranges and sensitivity tests.

4. Stop cherry-picking climate scenarios

Long-lived assets should be designed for at least a 2°C-consistent 2050 world, with stress-tests against higher warming pathways (3–4°C) and extreme tails.

A more practical way forward

For project teams, this shift can be translated into a clear set of steps:

- Begin by stating the asset’s design life and criticality classification.

- Select at least two SSPs and multiple horizons spanning the design life.

- Strengthen local granularity through climate vulnerability risk assessments tailored to the asset and its location.

- Test compound events and cascading failures.

- Incorporate climate allowances and identify low-regret measures.

- Document these decisions so future owners and operators can continue to adapt intelligently and with clarity rather than uncertainty.

The bottom line

We know with certainty that the years ahead will bring more flooding, heatwaves, wildfires, and emergencies. Design codes that rest on historical comfort can be a Trojan Horse in a changing climate, appearing safe while concealing future vulnerability. But if we integrate future climate intelligence into design today, embrace performance-based resilience, and plan for adaptation over time, that Trojan Horse can be transformed into a resilient vessel for foresight.

Want to know more?

Oliver Neve

Associate

+44 7870 808407

Lora Brill

Head of Sustainability - Buildings

Dale Tromans

Consultant

+44 7816 204102

Jukka Lahdensivu

Managing Consultant

+358 40 0733852